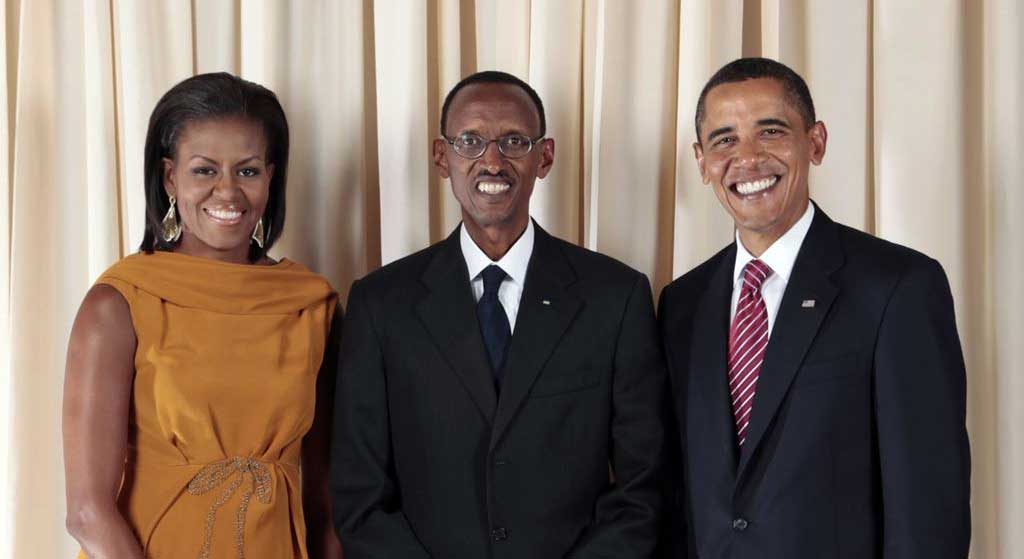

The international community has ensured legal immunity for Rwandan President Paul Kagame despite evidence of the RPF's responsibility for war crimes.

The 1994 Rwandan genocide has often been described as the fastest killing spree of the twentieth century, taking up to a million victims in a mere 100 days. One of the key drivers of the murders was fear: fear of an actual army in jackboots and fatigues encroaching by the day, but also fear of their allies on the ground, the so-called fifth column. In the first case, the fear was obviously justified: a Tutsi rebel army had invaded four years earlier and seemed poised to overthrow the Hutu-dominated government. Now newly uncovered evidence suggests another motivator – fear of Tutsi civilians – was also justified.

Several confidential documents from the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) provide chilling evidence that Tutsi civilians worked hand-in-hand with Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) to commit crimes against Hutus in 1994. The evidence from these documents is bolstered by lengthy interviews with individuals who witnessed these operations.

The ICTR documents refer to RPF’s abakada or civilian cadres and the ‘loyal population’ assisting the RPF in committing massive human rights abuses across the country. Abakada were Tutsi technocrats recruited before, during and after the genocide. They became the interface between the RPF on the one hand, and UN agencies, NGOs, human rights investigators and journalists on the other. The cadres played a crucial role in Rwanda’s statecraft and propaganda system after the genocide.

The crimes cited in UN documents included identifying prominent Hutus that would later be executed, locating and putting Hutus in dungeons, delivering Hutus over to RPF intelligence agents and digging mass graves to bury victims. The ICTR documents—which contain identifying information and cannot be made public—consist of testimony from former RPF members who broke with the regime.

Rwandans Betraying Each Other

The full horror of what happened in Rwanda in 1994 remains largely unknown in the West, although a significant amount of history has been well documented and verified. What we officially know is that Hutu hardliners and a portion of the civilian population exterminated Tutsis in locally organized massacres, as national broadcasts of Hutu RTLM radio demonized Tutsis and provided a degree of approbation the killers actively sought. Human rights groups, journalists and academics have estimated that at least 600,000 Tutsis were killed from April to July 1994. What shocked the world the most was the ‘popular element’ of the genocide—that Hutu peasants dared to kill their Tutsi neighbors and in some cases, members of their own families that were Tutsis. In his book The Order of Genocide, Scott Straus explores the profile of the genocide perpetrator. After conducting extensive research in Rwandan prisons, Straus posits that most of the murders of Tutsis were carried out by a small group of ‘extremely zealous killers, paramilitaries and soldiers.’ About a quarter of the murders were committed by ordinary Hutus, he says, estimating that seven to eight percent of the Hutu adult population, or 14 to 17 percent of adult Hutu males, actively killed Tutsis or Hutus opposed to the violence.

Yet there are eerie parallels between how the violence played out in Hutu government-controlled and in Tutsi RPF-controlled zones, and how Rwandans from both ethnic groups seemed ready to betray one another as soon as their president, Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was assassinated on April 6. Ultimately, with its top-down command structure and superior political organization, the RPF was better able to conceal its crimes and control the narrative.

Denouncing and Delivering Hutus in RPF-Controlled Zones

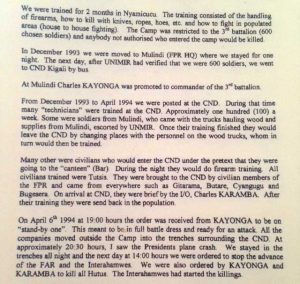

A civilian from Byumba in northern Rwanda who joined the RPF during the genocide gave detailed testimony on the role of civilian cadres to ICTR investigators. The prefecture of Byumba was largely controlled by the RPF at the outset of the genocide.

“As of April 8, 1994, there no were no (Hutu) ex-government soldiers in the region of Ngarama, prefecture of Byumba. RPF soldiers and cadres were monitoring the region. They began to enlist all young people into their ranks. At that time, murders and disappearances started. They began to target intellectuals and politicians that belonged to the former regime, and former mayors, town councillors, teachers and business people.”

The witness provided a partial list of victims killed, people he knew personally, including a Hutu agronomist who worked for the NGO Care International. He said the victims had initially run away from RPF forces but were lured back and promised they would be safe and could remain in their jobs. “In the end they were killed, just as they feared,” the witness said. The bodies were dumped in a mass grave near the Mugera market, he said, pointing out that countless peasants were also murdered in other locations throughout the commune.

In July 1994, units in every RPF battalion were operating dungeons and counted on the ‘loyal population’ to imprison Hutus they considered ‘Interahamwe’’—a Hutu militia that had killed Tutsis during the genocide. The witness said the ‘loyal population’ consisted of Tutsi genocide survivors and Tutsi refugees who had grown up in Uganda and were repatriated to Rwanda. “Former soldiers were arrested and executed in these dungeons, as were Hutu intellectuals, former regime members and all people considered obstacles, known as bipingamizi.”

“Civilians cadres were the ones who identified individuals to be delivered to soldiers. They did so according to their own interests. All soldiers had to do was kill.”

A second document compiled by ICTR investigators reveals the phenomenon of the ‘loyal population’ singling out suspects to be placed in dungeons. The investigators said that when the International Red Cross and NGOs became aware of the existence of the dungeons, the RPF moved the prisoners to other locations where they were executed.

A third ICTR document featuring testimony gathered in 2002 from a civilian cadre said many of his colleagues in Byumba were denouncing and delivering Hutus over to the RPF’s notorious DMI, the Directorate of Military Intelligence, as a matter of procedure. “There were disappearances in the refugee camps. People disappeared after being denounced by certain cadres. The cadres worked with their informants and reported back to DMI.”

A fourth ICTR document revealed similar testimony of DMI agents working with cadres in refugee camps to interrogate people suspected of being ‘extremists.’ The people who were interrogated, for the most part, ‘disappeared.’

A fifth ICTR document, dated 2005 and 54 pages long, describes in detail the killing operations carried out by Kagame’s forces in Giti, a commune where no genocide against Tutsis had been committed. The testimony from a senior DMI official stationed in Giti is downright grisly. He describes DMI mobile units arriving in Giti and neighboring Rutare in April, rounding up Hutu civilians and shooting them dead or hacking them with hoes. He said Tutsi volunteers were recruited into the RPF at a fast pace in these areas and helped dig mass graves. Many of the Tutsi civilians were called the Tiger Force. The Tiger Force would later plant banana groves over the graves in order to camouflage the sites, he explained.

The former RPF official said a network of ‘civil intelligence services’ was created upon the request of Kagame and Kayumba Nyamwasa, then head of DMI. This network was to work closely with DMI to gather intelligence within the civilian population.

Giti became a clearinghouse for murder, according to the DMI agent. Many Hutus were brought there from other areas and the RPF eventually ran out of room to bury the men, women and children they killed. The Hutus were ultimately transported by trucks to Gabiro, the RPF’s training wing at the edge of Akagera Park, where they were executed and burned.

The witness said he believed that Giti was simply one of many areas in Rwanda where the RPF committed systematic massacres of Hutus. When pressed by investigators, he admitted that Giti was a ‘tree that hid a wider forest.’

Other Testimony

A former resident of Giti interviewed by this journalist said his father, a prominent Hutu in the community, was seized and killed within a few days after the RPF established a base there in April 1994. To his horror he found his father’s body with several hundred other Hutus killed at Giti’s primary school. “The school courtyard was completely littered with corpses. And the classrooms inside were full. It was terrifying.” The witness, who is of mixed ethnicity with distinctive Tutsi features, said he was saved from being executed because of his mother was Tutsi and her relatives had ties to the RPF. He said he was appalled at how Tutsi neighbors he had known and trusted—people who had never been hurt by Hutus—identified and located Hutus in the village for the RPF to kill. They started with community leaders and moved onto peasants, he noted.

Another former RPF intelligence official that broke with the regime said he remembers Tutsi civilian cadres actively killing in Giti and Rutare. “A cadre named Martin grabbed a machete and took a Hutu aside, and cut his head off.” In many cases, soldiers and civilians watched as entire families were butchered, he said.

The former official alleges that civilian cadres came under the authority of the RPF’s political wing, known as the secretariat. The cadres’ role in eliminating Hutus was conceived by members of the RPF secretariat and the high command council, he insisted. There were an estimated 4,000 abakada in Rwanda during the genocide, and by the end of 1994, the RPF had recruited massively and increased their numbers to 15,000.

A soldier now in exile said his Tutsi family hid grenades at their Kigali home before the genocide, and that the RPF had successfully ‘infiltrated’ the capital and other areas of Rwanda, with cadres and commandos by 1993.

A former abakada who worked in RPF-controlled zones between April and July 1994 admitted there were three categories of cadres: those who provided social assistance and political indoctrination among the civilian population, a second category that assisted the war effort and facilitated crimes by denouncing and delivering Hutus over to death squads, and a third group of extremely zealous individuals who participated directly in the killings.

In an interview, the ex cadre said many civilian cadres were caught and killed in Hutu controlled zones before Kagame’s forces seized territory.

But in northern and eastern prefectures that came under RPF control quickly, cadres were free to carry out their dirty work, several sources confirmed. In other areas such as Gitarama, Butare and Ruhengeri, new cadres were recruited quickly in June and July, as those prefectures were seized by Kagame’s troops.

In the prefecture of Gisenyi, for example, vast areas were empty in mid July by the time the RPF took control; a significant number of Hutus had fled to Zaire by then. But some stayed put in their homes and eventually were slaughtered. A soldier with the RPF’s Charlie battalion said civilian cadres operated with DMI units in Gisenyi and eliminated as many Hutus as possible. Further north in Ruhengeri, DMI units massacred Hutus in July and August at Camp Muhoza and buried the victims in mass graves nearby, according to testimony from a former DMI agent given to ICTR investigators.

A soldier initially stationed in Byumba and later transferred to Kanombe said civilian cadres conducted widespread pillaging of Hutu properties and worked closely with political commissars in battalions. The political commissars would call bogus meetings, luring civilians and promising them food or security, only to have them killed afterward, the soldier explained.

“In some cases, civilians were more extreme and zealous than the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) was. The rank and file RPA soldier was trained for battle. The political commissars and civilian cadres who chose to work with DMI had other intentions,” he said.

The soldier said the role of abakada and even Tutsi survivors in crimes is well known but never spoken of inside or outside Rwanda. He alleged that a good number of Tutsis are vehemently opposed to Kagame but are afraid to talk about the past because they are not willing to implicate themselves. “Kagame holds this over their heads.”

“And Hutus have been completely silenced on the issue.” Hutus in Rwanda and abroad who dare accuse the RPF of crimes end up in jail, disappear or are charged with genocide, he noted.

And yet Hutus and Tutsis have given crucial testimony to the ICTR and the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) about these atrocities.

A Hutu refugee gave the UNHCR the names of a dozen Tutsis, comprised of abakada and neighbors that killed his teenage sister in April 1994 in the commune of Gituza. He described the Tutsis as a kind of militia, not unlike the Interahamwe. He said the Tutsis were armed with hoes and machetes when they brought his sister to their home while he hid in the garden behind the avocado trees, paralyzed by fear. He then listened in agony as they raped her, one by one, and set the bedroom on fire before leaving the premises. When he rushed in after they left, his sister was dead. The refugee fled to Tanzania, reported the crime but received no justice. The Tutsis responsible still hold prominent positions in the community, he said.

A UN court set up to prosecute perpetrators of genocide and serious violations of international law has protected Kagame and his senior commanders: not one indictment against the RPF has ever been issued. In contrast, 95 individuals linked to the former Hutu regime were indicted and 61 were convicted.

Kagame Given Criminal Reign

The international community has ensured legal immunity for Kagame and allowed his regime to commit crimes after the genocide, both in Rwanda and in neighboring Congo, where he invaded in 1996 and his troops were accused by UN experts of possibly committing genocide.

A senior Tutsi officer who fled in 2000 said the RPF recruited and eliminated thousands of young Hutu men in late 1994 and 1995, using civilian cadres in the campaign. The cadres worked with the gendarmerie, presidential guard units, the training wing and DMI agents to recruit and then execute these men, mostly in military camps but also in Akagera Park, he said. “It was done efficiently everywhere.” By that time DMI operations were headed by Emmanuel Karenzi Karake.

Dozens of soldiers and officers interviewed insist that the RPF killed hundreds of thousands of Hutu civilians during and after 1994, in addition to Tutsi francophone recruits that were considered suspect by intelligence officers at the training wing.

Several people interviewed said the RPF civilian cadres continue to wield power in Rwanda but are now called the intore. Over the last two decades, thousands of people—both Hutu and Tutsi—have been trained in secret camps at Nasho and Ndego in the Akagera. The intore work at home and abroad, and are comprised of nurses, doctors, teachers, university staff, bankers, taxi drivers, among other professionals. Most are trained to spy on Rwandans in all walks of life but some intore are given specialized training to assassinate and commit other crimes, the sources said.

Nowhere in Rwanda is the state’s presence felt more acutely than at the local level through a neighborhood surveillance system called Nyumbakumi. The Nyumbakumi uses agents from military, political and civilian spheres to exert control: DMI agents, RPF secretariat members and their civilian auxiliaries known as intore monitor every 10 households.